|

| Bev Thomas, Rivers of Time 15cmx15cm. |

Sunday, November 12, 2017

Tuesday, November 7, 2017

Installation of Trees: As Above So Below No 4

Installation of Trees: As Above So Below No 3

Installation of Trees: As Above So Below No 2

Installation of Trees: As Above So Below No 1

|

| Janet Meaney, Upside Down 2017 |

|

| Janet Meaney, performance 2017 |

|

| Janet Meaney, performance 2017 |

Inga Simpson's opening talk for Trees: As Above, So Below

|

| Inga Simpson |

It is my great pleasure to launch this exhibition. Trees: As above, so below.

We’re finding out a lot more about trees lately. Scientists have shown that trees communicate with each other via underground fungal networks, that they can adapt to threats, work together, and even recognise one human from another. But some of us already knew this. Artists and writers and tree-people have always known it, felt it, and explored it in their work. Still, it is nice to be proven right.

There is as much tree below ground as above it. Their roots stretch downwards and outwards, away from the light and towards rock, soil and water, drawing life out of earth. While trees appear silent and still, their growth too slow to observe, except by marking their changes over time, they are always moving beneath the surface. Water cycles up and nutrients circulate down. The tree is earth and the earth is tree.

With its roots in the soil and crown in the sky, it makes sense that in many mythologies, a cosmic tree was the backbone of the earth, the trunk passing through the world and crown stretched out over the heavens, hung with stars.

Perhaps the wisdom of trees comes from the ground itself, from being so deeply anchored to country. Connected, as they are, to the greater machinations of the earth – the slow-moving bedrock of seasons, years, ages, millennia. To a tree, the daily affairs of humans must seem peripheral at best.

But there is more to us than meets the eye, too. Things going on below the surface, in our brains, the receptors on our skin, in every cell. There is our physical self, and the things we feel sure of: our jobs, houses and families, our electricity bills, what’s on the news and in our fridges. And then there is the rest: the mysterious, the felt, the intuited, the imagined, the dreamt and the remembered.

When Janet contacted me about launching this exhibition, I was working overseas, and trying to have a break from my email and from commitments that keep my away from my desk. But the mention of trees and the botanical gardens got my attention. One of the lovely things about being published and focusing on trees and birds, and even going so far as to call myself a treewoman, as I have in Understory, has been the synergies that seem to line up, with other writers and artists, and projects, and the people that come along to events like this.

I’ve always envied visual artists, the chance to work with tangible materials, to make something you can see, that people can respond to more immediately and walk around and talk together about. My second book, Nest is about a bird artist who builds a nest for herself. A piece that wouldn’t be out of place in this exhibition.

When my own creative juices are running low, I do two things: I take a long walk in nature, usually a forest. I need that. To rejuvenate. And I go to a gallery – and wander through an exhibition. Something new. Or a new take on something old. It doesn’t matter. It fills me up again, shifts my perspective, just a little, and gets me thinking, imagining, creating again. With Trees. As above, so below, I can do both. The gallery is outdoors. I can walk among trees and see a range of works and installations from a group of very talented artists working in different mediums. Applying their imaginations to a theme with a variety of results.

Works like this are particularly important at the moment. They help close the gap between us and the natural world, reminding us that although many of us have become a bit estranged from it, locked up in apartments and offices and cars, we are part of nature, we are only animals that have developed some skills at the expense of others, and – in my view – have already squandered many of the riches on this planet. And it will cost us, not just in the loss of species and diversity among the flora and fauna that we define ourselves by, but in our own quality of life – and even our own existence. After all, this is our habitat, too.

Eco-critic, Lawrence Buell, in his book The Environmental Imagination, argues that it is a lack of imagination that has brought us to the brink of environmental disaster. And so, it makes sense that it is imagination that will lead us out of it. Allowing us to reimagine our relationships with the natural world, and to conceptualise more sustainable futures.

Traditional cultures don’t draw a line between nature and culture, human and nonhuman. It is artificial. A construct of science, of Christianity, and of capitalism – it is convenient isn’t it, to conceive of ourselves at the top of the food chain and everything else a resource to be consumed, eaten, and experimented on. And to take no responsibility for the wellbeing of other creatures, of our environment. The study of ecology has shown us the ways in which everything is connected, a delicate interconnected set of ecosystems, which we are very much a part of. Human actions impact on these ecosystems.

And they impact on us. We’ve known this for a long time. Artworks and writing which foregrounds nature and highlights this connectedness are called ecological – it’s not new but it’s still a little revolutionary, challenging the dominant way of thinking.

So as you walk among these works today – which are in themselves ecological, working together, with the environment, to communicate with each other and with you – maybe try and see the world without that division between us and them for a moment. Imagine yourself a little more tree, your roots extending deep into the earth, and tapping into what you know and feel but might be afraid to believe. Taking up a little of the wisdom and calm we could all do with to enrich our lives. The art of taking the long view.

So, congratulations to all of the artists involved. It is my great pleasure to pronounce this exhibition, Trees: As above, So below – officially launched.

Inga Simpson 14 October 2017

Saturday, October 7, 2017

Thursday, October 5, 2017

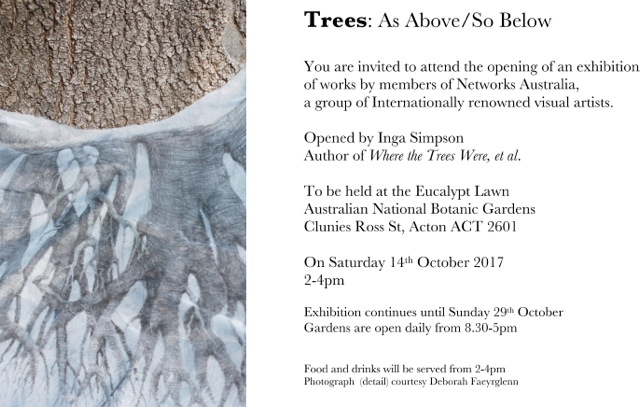

Trees: As above, So Below

The artworks visible on and around the Eucalypt Lawn are part of an exhibition titled Trees: As above, So Below, created by members of Networks Australia, a group of primarily Canberra based visual artists who have exhibited extensively nationally and Internationally, addressing a variety of issues, social, political and environmental.

In this instance inspired by the work of the ANBG and a slew of recent books on the subject of trees, 1 the artists focus on the broader and often overlooked if not hidden aspects of trees to expand perceptions beyond the visible structure to root systems and canopies and various interdependences and interactions with other life forms vital in maintaining a healthy eco-system.

|

| Bev Moxon |

|

| Deborah Faeyrglenn |

|

| Members discussing Trees: As above, So Below exhibition works |

|

| Nancy Tingey |

|

| Rozalie Sherwood |

Saturday, September 16, 2017

Dr Suzanne Simard's how trees talk to each other

Two links with a talk and an interview with Dr Suzanne Simard supplied by Deborah Faeyrglenn about Tress and their ways of communicating with each other.

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

TED TALK

"A forest is much more than what you see," says

ecologist Suzanne Simard. Her 30 years of research in Canadian forests

have led to an astounding discovery -- trees talk, often and over vast

distances. Learn more about the harmonious yet complicated social lives

of trees and prepare to see the natural world with new eyes.

This talk was presented at an official TED conference,

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Interview with Yale Environment 360 and Dr Suzanne Simard Exploring How and Why Trees ‘Talk’ to Each Other

Ecologist Suzanne Simard has shown how trees use a network of

soil fungi to communicate their needs and aid neighboring plants. Now

she’s warning that threats like clear-cutting and climate change could

disrupt these critical networks.

Two decades ago, while researching her doctoral thesis, ecologist Suzanne Simard discovered that trees communicate their needs and send each other nutrients via a network of latticed fungi buried in the soil — in other words, she found, they “talk” to each other. Since then, Simard, now at the University of British Columbia, has pioneered further research into how trees converse, including how these fungal filigrees help trees send warning signals about environmental change, search for kin, and transfer their nutrients to neighboring plants before they die.

By using phrases like “forest wisdom” and “mother trees” when she speaks about this elaborate system, which she compares to neural networks in human brains,

Simard’s work has helped change how scientists define interactions between plants. “A forest is a cooperative system,” she said in an interview with Yale Environment 360. “To me, using the language of ‘communication’ made more sense because we were looking at not just resource transfers, but things like defense signaling and kin recognition signaling. We as human beings can relate to this better. If we can relate to it, then we’re going to care about it more. If we care about it more, then we’re going to do a better job of stewarding our landscapes.”

Simard is now focused on understanding how these vital communication networks could be disrupted by environmental threats, such as climate change, pine beetle infestations, and logging. “These networks will go on,” she said. “Whether they’re beneficial to native plant species, or exotics, or invader weeds and so on, that remains to be seen.”

Read full interview

Two decades ago, while researching her doctoral thesis, ecologist Suzanne Simard discovered that trees communicate their needs and send each other nutrients via a network of latticed fungi buried in the soil — in other words, she found, they “talk” to each other. Since then, Simard, now at the University of British Columbia, has pioneered further research into how trees converse, including how these fungal filigrees help trees send warning signals about environmental change, search for kin, and transfer their nutrients to neighboring plants before they die.

|

Beiler et al 2010

A diagram of a fungal network that links a group of trees, showing the presence of highly connected “mother trees.”

|

By using phrases like “forest wisdom” and “mother trees” when she speaks about this elaborate system, which she compares to neural networks in human brains,

Simard’s work has helped change how scientists define interactions between plants. “A forest is a cooperative system,” she said in an interview with Yale Environment 360. “To me, using the language of ‘communication’ made more sense because we were looking at not just resource transfers, but things like defense signaling and kin recognition signaling. We as human beings can relate to this better. If we can relate to it, then we’re going to care about it more. If we care about it more, then we’re going to do a better job of stewarding our landscapes.”

Simard is now focused on understanding how these vital communication networks could be disrupted by environmental threats, such as climate change, pine beetle infestations, and logging. “These networks will go on,” she said. “Whether they’re beneficial to native plant species, or exotics, or invader weeds and so on, that remains to be seen.”

Read full interview

Birds Nest in Arnhem Land

Friday, September 15, 2017

Rainforest Book

Tuesday, September 12, 2017

Crown Shyness

The Phenomenon Of “Crown Shyness” Where Trees Avoid Touching

By Christopher Jobson

Crown shyness

is a naturally occurring phenomenon in some tree species where the

upper most branches in a forest canopy avoid touching one another. The

visual effect is striking as it creates clearly defined borders akin to

cracks or rivers in the sky when viewed from below.

Read full article

|

| Photo © Dag Peak. San Martin, Buenos Aires. |

|

| Photo © Dag Peak. San Martin, Buenos Aires. |

Lesley Richmond

As the Networks group is looking at Trees as a theme at the moment, there is a very interesting interview with Lesley Richmond on Textileartist.org Textileartist.org has interesting interviews and information for contemporary textile artists.

Lesley Richmond was born in Cornwall, England. Lesley now lives in Vancouver, BC, Canada.

Textileartist.org

Lesley Richmond

Lesley Richmond was born in Cornwall, England. Lesley now lives in Vancouver, BC, Canada.

|

| Lesley Richmond, Winter Series Moonlight Mandala 84cm x 140cm image from artists Website |

Textileartist.org

Lesley Richmond

Thursday, April 6, 2017

Tuesday, March 21, 2017

Golden Orb Spider and Magpie Nest

Magpie Nests at the National Arboretum ACT

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)